Whether you grow your own vegetables, frequent farmers’ markets, or grocery shop, you’ve no doubt noticed an increase in the quantity and quality of tomatoes. Yes, it’s tomato time, the period from July to October where locally grown, vine-ripened tomatoes hit their prime. For those who happily chomp on tomatoes as a snack, salad, side or main dish, it’s a highly anticipated season. For those like me who don’t share this passion, it means confronting the quandary of what to do with all those tomatoes.

A well-meaning friend once suggested that I try canning them. After all, doesn’t everyone love home preserving? Apparently not. After one steamy, day-long canning class I learned that, like oil and water, canning and Kathy do not mix.

After ruling out canning, I considered other options, including drying tomatoes in a food dehydrator. While pleasant tasting, dried tomatoes lacked the spark of their fresh, juicy brethren. Realizing that, I scratched dehydrating from my list.

Ultimately, I’ve opted either to cook them or to serve them raw in an endless parade of recipes. Lucky for me, tomatoes pair well with almost everything. They possess a special affinity for such fruits and vegetables as arugula, bell and chili peppers, cucumbers, fennel, garlic, lemon, onions, shallots and watermelon but also partner nicely with avocado, green beans, broccoli, cauliflower, eggplant, mango, mushrooms, peas, raspberries, squash and zucchini. Their sweetly sour flavor compliments bay leaves, cilantro, marjoram, mint, flat-leaf parsley, black and white pepper, and thyme.

Likewise, tomatoes go with a variety of cheeses – blue, goat, Gorgonzola, mozzarella, Parmesan and ricotta among them. They also marry successfully with balsamic, red wine, rice, sherry, tarragon and white wine vinegars as well as with olive oil and salt.

Along with countless flavor affinities, tomatoes offer a great degree of cooking versatility. They’re wonderful when baked, broiled, fried, grilled, sauteed, stewed, turned into a sauce or served raw. With the exception of plum tomatoes, which have a fairly tough skin, they don’t require peeling or de-seeding. Just slice and serve them with a dash of salt and black pepper. Easy!

When faced with a huge mound of these veggies, I dig out my stack of tomato-oriented recipes and get to work. Sometimes I’ll plunk them into my food processor and, after adding cucumbers, peppers, garlic and sherry vinegar, make gazpacho soup. I’ll also plop them into a stockpot with chopped garlic, onions and basil and simmer a peasant-style pasta sauce. With smaller amounts I may pull out a sheet of frozen puff pastry, cover it with sliced tomatoes, and bake a tomato tart. I often just layer sliced tomatoes between fresh basil, grilled Haloumi cheese, and thick slices of multigrain bread or grill them with a little goat cheese on top for a tasty Mediterranean lunch.

GRILLED MEDITERRANEAN TOMATOES

Serves 2 to 4

2 tablespoons olive oil

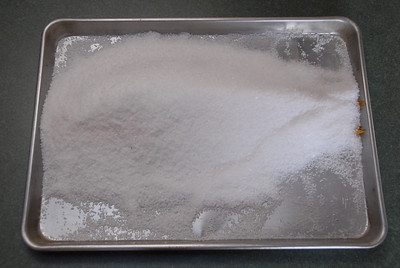

2 large, ripe tomatoes, cored and sliced

1/8 to ¼ teaspoon dried oregano or to taste

1/8 to ¼ teaspoon dried basil or to taste

3 ounces goat cheese

dash of freshly ground black pepper

Preheat the grill on high.

Tear off a large sheet of aluminum foil and spread 1 tablespoon of olive oil over it. Place the tomato slices on the greased foil. Sprinkle dried oregano and basil over each slice and then drizzle the remaining olive oil over them. Using a spoon or your fingers, distribute equal amounts of goat cheese on each tomato and then season with ground black pepper.

Lay the foil on the heated grill and allow the tomatoes to cook for 5 minutes or until the cheese has melted slightly and the tomatoes have released some of their juices. Serve the tomatoes on their own or atop steamed couscous.